Expertly and compassionately handled, the managed move can transform the life-chances of vulnerable young people but, as in all things, there is a spectrum of practice and safe transition onto the roll of the new school is far from guaranteed. With every school move, every social and educational disruption, the pupil’s odds of positive outcomes reduce, so it is important that leaders proactively invest in the process, rather than merely opening their doors and reaching a decision at the end of the agreed trial period as to whether or not the required behavioural standard has been met.

In many ways, it is those young people with the least resilience who are required to navigate the most moves. A harmful cycle of failure can result from this, unless it is interrupted. Ella, who agreed to my recording and sharing the interview below, is no exception. She ‘failed’ two placements before finding her educational home at the third, a mainstream school which wrapped support around her for as long as she needed it.

Her reflections on what made the difference form the basis of the five recommendations outlined within this post, alongside findings from the Education Endowment Foundation’s Improving Behaviour in Schools and insights from the trauma-informed practice field.

- Ask what happened to you?

Without wishing to prompt a futile debate about whether or not all misbehaviour communicates an unmet need, it is reasonable to suggest that chronic behavioural difficulties should always invite professional curiosity. Because of the proven impact of childhood adversity and trauma on the nervous system and subsequently emotional regulation, we need to ask “What happened to you?”

Ella talks about her experiences of relational trauma: the separation of her parents and subsequent loss of ‘my main person at home’, conflict, multiple losses from an early age, moving to a different country and feeling the outsider. With some distance, and now balanced, she recognises how sensitised she was when struggling in school, unable to tolerate mild stressors, such as a teacher’s reprimand. Any one of us who has experienced high levels of stress at certain points in our lives can relate to this. We know from our own experience – even as adults with the frontal lobe fully matured – that judgement is impaired when we are cortisol-flooded.

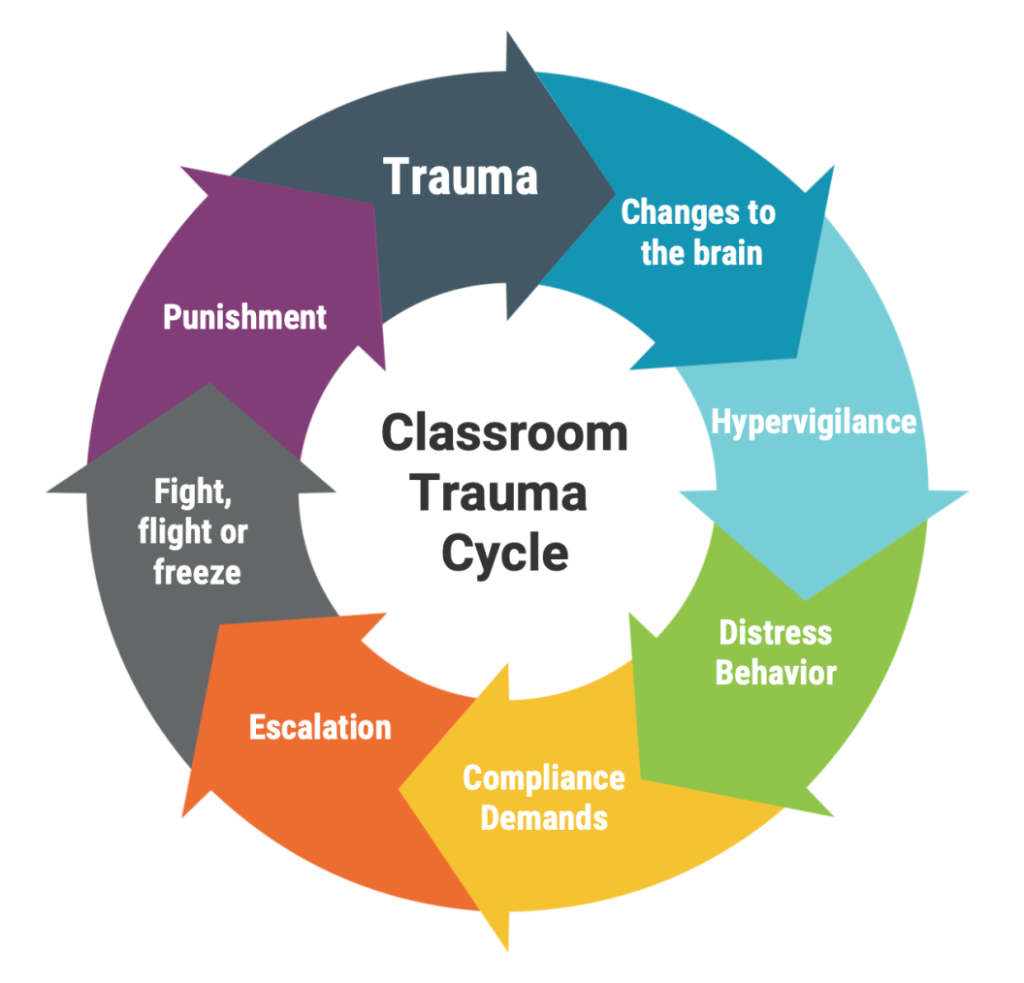

Knowing ‘What happened to you?’ enables staff to interpret misbehaviour through a trauma-informed lens so that the response can be moderated, which will in turn alleviate the issues. All staff have a vital role to play as stress managers rather than merely behaviour managers, breaking the insidious classroom trauma cycle through their compassionate understanding. Sharing information – a pupil’s trauma history – is therefore important, so far as confidentiality allows.

2. Prioritise relationships

The teacher who spotted Ella standing on her own that cold morning must be given enormous credit for the part she played in changing her life. Offering the sanctuary of her classroom and unstinting kindness, she was the place of safety during those challenging early weeks when Ella would otherwise have felt, once again, the outsider.

The fact that she had no formal responsibility for Ella is worth considering in relation to the critical role of trusted adult: “Mrs. Brown will be your trusted adult and you can find her if you have any problems in R6” is not that. When school leaders invest in and promote social capital, these roles form in an organic way, as authentic human relationships. For a pupil who has experienced relational trauma and therefore struggles to trust, they should be viewed as key interventions.

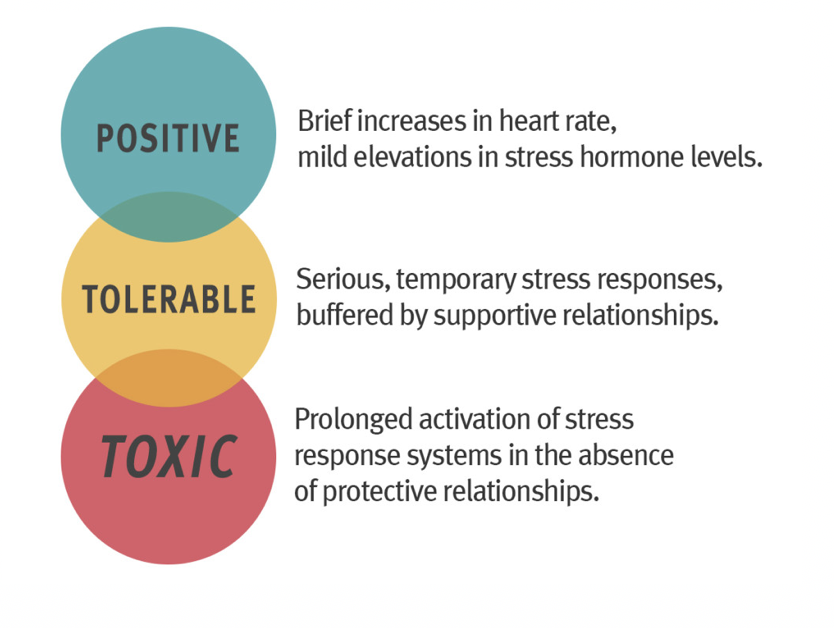

Ella observes that “they listen to us here” – which tells us everything we need to know about the quality of that nurturing school community. Any pupil undergoing a managed move should be encouraged to talk about their challenges because it is through talking that we habituate stressful experiences which might otherwise overwhelm. This is what is meant in the trauma-field as the ‘social buffer’ against toxic stress.

It is no stretch to suggest that the success of any managed move will depend upon the quality of the relationships that a pupil forms, even if these develop accidentally rather than by design. The EEF recommends a strategic approach: “Is it possible to structure your school such that everyone knows each pupil, their strengths and interests? Can this be managed for some pupils, if not all?

3. Create the conditions for psychological safety

Even for adults, major transitions are stress inducing. That’s because of an unconscious process called neuroception which keeps us safe by constantly scanning the environment for threats. From birth, we categorise incoming sensory data as safe or unsafe, our emotional triggers resulting from subsequent encounters with the latter. In addition to triggers, or evocative cues, novelty is activating in that, as Perry explains, new experiences are classified as potential threats until proven otherwise.

“Anything new will activate our stress response systems. Our default response to novelty is ‘Uh oh. What is this?’ And until the new thing is proven safe and positive, it will be categorised as a potential threat. For most people, the unknown is one of the major causes of feeling anxious and overwhelmed.”

Here we arrive at the key concept of psychological safety. This is enhanced by predictability, so a calm and orderly school climate is essential. In the full version of the interview, Ella explains that she researched the school before she started there, so that it was at least a little familiar. The fact that her initial visit was during lockdown will also have helped; there were fewer new faces to categorise as friend or foe. She was able to focus on getting to know just a handful of key people.

It is worth thinking about how these conditions might be replicated under more normal circumstances; how a carefully phased induction period might allow gradual exposure to novelty such that the nervous system is able to maintain balance.

4. Differentiate the behaviour policy

The crude concept of ‘consistency’ does our most vulnerable learners a grave disservice. Here is the fifth of six key recommendations within the EEF report:

Ella’s previous encounter with an inflexible behaviour policy increased her isolation and loneliness, and with that her risk. Any incidents must be addressed, of course, and boundaries must be maintained, but the ‘how’ matters. Kim Golding’s ‘Connection before Correction’ is the best tool we have for empathic boundary setting and staff will need to avoid any behaviourist short-cuts if psychological safety, which takes time to establish, is not to be compromised. If removal from class is necessary, that should not be to isolation and exclusions can fatally undermine that greatest of all protective factors, a sense of belonging.

Perry is clear about the risk of social thinning, which any pupil undergoing a managed move will experience. A behaviour policy which aggravates that will fail on its own terms, separation from the group being interpreted by the survival brain as a threat to life. Vulnerable pupils need attuned others, access to co-regulating adults – not solitary reflection or undifferentiated consequences. As part of the managed move plan, it is important to agree how setbacks will be managed so that there is learning from them.

5. Aim for intrinsic motivation

There is a risk that the incoming student, not yet one of us, may be held to a higher standard of behaviour than the rest of the school community. There may be closer scrutiny, perhaps a report card measuring progress towards externally imposed targets, such as “Follow all instructions, first time”. We can be reasonably sure that this approach will not work because it will have been tested over a prolonged period in the previous setting already, without success. Any student on a managed move will benefit from not just a fresh start, but a fresh approach – aimed at promoting intrinsic motivation.

Teachers can use tangible techniques such as rewards and sanctions, or less tangible strategies such as praise and criticism, to improve motivation, behaviour, and learning. However, it is intrinsic motivation, or self-motivation, that is crucial to improving resilience, achieving goals, and ultimately is the key determiner to success. Children who are intrinsically motivated achieve better and are less likely to misbehave. (EEF)

Coercive tactics can rarely meet the needs of young people who have experienced trauma. Trauma is very often, after all, the experience of utter powerlessness and the need for control when that is the case is acute. Extrinsic motivators – pressures applied from without to illicit desired behaviours – should therefore be avoided, counter-intuitive as that may feel.

Ella’s initial meeting with the headteacher clearly inspired feelings of intrinsic motivation which got her trial placement (not emphasised as such) off to the best possible start. There was no report card, no monitoring arrangements – at least not that she was made aware of – but instead the offer a prefect’s tie. Conditions were not attached, this was not a bribe; the headteacher merely recognised a need – to be trusted, heard, valued – and found a way of meeting it. The impact of this simple gesture was profound and lasting.

Ella turned out to be a gifted mathematician and secured top grades despite her fractured journey through secondary education. Once she had access to buffering relationships, unconditional positive regard, when she was trusted, heard and valued, she flew. Her story perfectly illustrates Alexander den Heijer’s truth – that “When a flower doesn’t bloom, you fix the environment in which it grows, not the flower.”

The managed move can heal, but equally it can harm, and everything in between. Ella experienced the full spectrum of practice and this for me is what makes her testimony so important. Her transformation was rapid; the young brain is a sponge for learning – highly malleable; shaped and sculpted through interaction with the environment. There is hope in that. We should always be optimistic about the prospect of a managed move to change lives and of course never write young people off.